- 公式HPリンク

- トータルエンジニアリング

- SAKE Brewery Interview (酒蔵記事)

- 記事制作について

- The Art of Sake Brewing 1

- The Art of Sake Brewing 1(ENG)

- The Art of Sake Brewing 2

- The Art of Sake Brewing 2(ENG)

- The Art of Sake Brewing 3

- The Art of Sake Brewing 3(ENG)

- The Art of Sake Brewing 4

- The Art of Sake Brewing 4(ENG)

- The Art of Sake Brewing 5

- The Art of Sake Brewing 5(ENG)

- The Art of Sake Brewing 6

- The Art of Sake Brewing 6 (ENG)

- The Art of Sake Brewing 7

- The Art of Sake Brewing 7 (ENG)

- 設備デザイン

- 展示会・セミナー

- FTIC(未来技術革新委員会)

- 補助金サポート

- 生産性向上要件証明書

- 微生物インダストリープラットフォーム

- Enz Koji

- 一般食品

- お問い合わせ

The Art of Sake Brewing (vol.7)

The 13th successor’s “inheritance and innovation” that birthed the new “Shichiken” brand.

Tsushima Kitahara , President & CEO, Yamanashi Meijo Co., Ltd.

[インタビュー内容]

Spanning from Edo period to Reiwa, Yamanashi Meijo—the brewery of the sake brand Shichiken—has always brewed alongside the pristine waters of Hakushu since its founding in 1750. To pass its history and culture on to the next generation, Tsushima Kitahara, the 13th head of the Kitahara family, has launched a full rebranding centered on water. His initiatives range from developing sparkling sake to forging cross-industry collaborations.

Tsushima Kitahara , President & CEO, Yamanashi Meijo Co., Ltd.

Why Tell the Brewery’s History?

Along the old Koshu Kaido—one of the five major roads that once connected Edo with the rest of Japan—stands a striking wooden building. A sugidama (cedar ball) hanging from the eaves signals to passersby that it is a sake brewery. Beside it, a sign boldly reads “七賢 (Shichiken),” while the noren curtain carries the double crest of the Kitahara family, who have run Yamanashi Meijo for generations.

The origins of Yamanashi Meijo date back to 1750, when Ihei Kitahara, the first-generation head, branched off from the main Kitahara family—also brewers in Shinshu (present-day Nagano Prefecture)—and established a new brewery along Koshu Kaido. He was captivated by the exceptional water of Hakushu. The main house of the new Kitahara family, built in 1835, still has the original ranma transom of the "Seven Wise Men of the Bamboo Grove." In 1925, the 10th head of the family formed Yamanashi Meijo Co., Ltd., and launched the Shichiken (Seven Wise Men) brand after the transom.

On June 22, 1880, during an imperial tour, the main residence served as a temporary lodging (anzaisho) for the Meiji Emperor—then still revered as a living deity. As a result, the space was preserved for decades as a historic site. Although that designation was removed after WWII with the Emperor’s renunciation of divinity, the building remains a valuable cultural asset and is carefully maintained by the family.

Kitahara speaks passionately about the brewery's historical background:

"This building once housed a bank, and it was even used for public hearings. Sake breweries were expected to play far greater social roles in the past than they do today, and we fulfilled those roles. Because sake is a luxury drink, it’s not enough to simply make something delicious—we need to convey the history and the culture behind it."

Water: The Only Ingredient That Has Never Changed

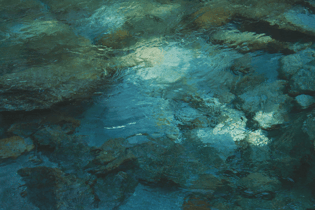

Hakushu, located at the foot of Mount Kaikoma in the Southern Alps, is renowned throughout Japan for its mineral water. Roughly 35% of all bottled mineral water in Japan is sourced from this town. Snowmelt from Mount Kaikoma filters through granite over more than 20 years before emerging as exceptionally soft water with a hardness of just 20.

“Soft water is not as suited for vigorous fermentation as hard water, but it’s perfect for making fruity, refreshing sake. The spring water of Hakushu is the only ingredient that has remained unchanged for nearly 300 years. Especially now, when rice and brewing techniques have evolved dramatically, I realized how important it is to acknowledge the value of our water.”

To draw out the character of this water, the brewery has focused on fruity and fresh styles since 2014, refining its entire product lineup. Kitahara emphasizes two key commitments:

The first is to incorporate top-tier techniques into mass production. Yamanashi Meijo installed a series of “Ginjo-kura” equipment by Fujiwara Techno-Art, fully quantified and stabilized its brewing process for all products, and aimed to achieve high quality across all products, not just premium labels.

The second commitment is to complete all products as undiluted sake, with no water added. Every product is bottled undiluted at around 15% ABV and pasteurized only once before refrigerated storage.

“Time and heat are the greatest enemies of fresh sake, so we extend our brewing periods across three seasons to ensure we ship everything at peak freshness—both domestically and internationally.”

The brewery uses only local rice—Yume Sansui and Hitogokochi—grown with the same water that brews their sake. They purposely avoid Yamada Nishiki, the “king of sake rice,” not to compete by rice variety or polishing ratio but to create sake that could only be made here. Shichiken brewed with Yume Sansui has won gold at the Japan Sake Awards for two consecutive years.

Looking back on the turning point in 2014, Kitahara says,

“Once we recognized the value of our water, the sake we needed to make became clear. From there, our brewing methods, branding, sales channels, and strategy all fell into place.”

The results speak for themselves: Shichiken has earned recognition worldwide, with its Junmai Daiginjo Hakushin winning Champion Sake at the 2025 International Wine Challenge (IWC).

Make Sake Unforgettable —But Don’t Turn It Into an Artwork

Kitahara stresses the need for a sustainable business model. Sake consumption has steadily declined since its 1973 peak—now just one quarter of what it once was. Of Japan’s roughly 1,400 breweries, many face financial difficulties. Sake accounts for only about 4.6% of the domestic alcohol market and less than 0.1% globally, despite its UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage designation.

“Our mission isn’t just to make delicious sake. People need to drink it, be moved by it, and remember it. But we must avoid turning it into artwork for its own sake. There are sakes that prompt people to say ‘delicious!’—yet many people still never try sake at all. Instead of limiting supply and relying on scarcity, we need to expand quantity while increasing value. That’s why we’re committed to improving our brewing techniques.”

Creativity, he says, is essential.

“How can we make better sake? How can we share it with more people? What machinery should we use, and how? By constantly asking these questions, we can achieve both volume and value. Brewers sacrifice sleep for Japan Sake Awards in pursuit of the perfect method—once that method is established, why not apply it to volume products? It’s like applying F1 technology to a Toyota Corolla.”

【Shichiken product line has a unique pricing philosophy. The price range is from 1,000 yen to 50,000 yen. While demonstrating value in the higher price range, it also attracts entry-level customers and broadens its reach.】

Even as the brewery pursues top quality across the lineup, its workforce cannot grow indefinitely.

“We achieve the brewing we envision by working closely with equipment manufacturers and incorporating the right machinery,” Kitahara says.

For example, Fujiwara Techno-Art's series of “Ginjo-kura” equipment is used throughout raw material processing, raising quality while reducing labor.

"Rotary automatic rice washing and soaking device cleans rice extraordinarily well—the soaking water becomes almost transparent, beyond what hand-washing can achieve,” he says.

He also praises the koji and cooked material transporting equipment, which improves hygiene, cuts labor, and significantly boosts quality.

This device transports koji and rice mixed with the brewing water, reducing the work of stirring the mash.

Kitahara emphasizes, “For us—striving to make all of our sake ginjo-style—it’s indispensable. To bring out the flavor of Shichiken, the fermentation must be as slow as possible in the early stages. Stirring the mash can be beneficial in some cases, but can also have a negative effect in other cases. This device provides us with moderate mixing.”

He adds:

“With today’s shrinking workforce, relying solely on manual labor has clear limits. Machinery helps eliminate variation and improves efficiency. Even considering initial costs, this equipment will greatly impact the management of breweries producing 541,000 liters or more.”

The Brewers’ Essential Skills

By mechanizing and systematizing processes, Yamanashi Meijo can now make decisions based on both quantitative and qualitative indicators. Conditions such as weather and rice quality change annually. This allows frontline brewers to make flexible decisions aligned with management policies, even when weather conditions or rice quality change.

Kitahara says brewers must excel at noticing and responding to outliers. Even with precise data management—temperature, humidity, weight—the moment of discovering an anomaly still relies on human senses and experience. Resolving it requires persistence and passion.

“Spirit and passion are the most important qualities I look for. Academic knowledge helps, but the determination to make better sake is far more valuable.”

【Today, Yamanashi Meijo produces 667,400 liters annually with nine employees—effectively six when rotating shifts—and guarantees 115 days of annual leave. A workplace where young talent can thrive long-term, Kitahara says, is essential to sustaining the industry. (Photo: Tezuka, Section Manager, Production Department.)】

Equally essential is a strong partnership with machinery manufacturers.

“Fujiwara Techno-Art is hands-on and understands brewing. They customize solutions and rush to help when needed—all with the spirit of a local workshop. Recently, rice was spilling from a cooler; they fixed it with a cover and a small adjustment, drastically reducing losses and fully repaying our investment.”

“It’s Time for Sake to Be Inspired by Other Alcoholic Beverages”

“inheritance and innovation”—Kitahara repeated these words throughout the interview.

“To pass Japanese sake culture on to the next generation, we must preserve tradition while continuously embracing new challenges.”

Sparkling sake | Products | SHICHIKEN|Yamanashi Meijo Co., Ltd.

【The lineup of sparkling sake has a wide range of prices, from "Yama no Kasumi" (720ml, ¥1,980) to "Shichiken Sparkling Sake Expression 2020" (¥55,000), which uses 40-year-old aged sake as part of its brewing water.】

He shared techniques with other breweries seeking innovation and also learned from wineries and whisky distilleries in Yamanashi.

“Sake brewing techniques are already highly refined. Now it’s time for sake to draw inspiration from other liquors. Sparkling sake is still in its infancy, but we’re pursuing distinctive ideas—whisky-barrel aging, kijoshu-based creations, and more.”

While learning from other alcoholic beverage cultures, Kitahara emphasizes that "sake is the foundation —the trunk of this brewery." Sparkling sake is completely different from sparkling wines. Sparkling sake has the potential to build its own unique market and culture.

*kijoshu: a special type of sake brewed with sake instead of water.

“Sake Is a Growing Industry”

Kitahara believes the potential for growth is enormous.

“In Japan, many people don’t drink sake—meaning the market can still expand significantly. Overseas, too, there is huge untapped demand.”

Rather than competing for the small group who already drink sake, he intends to reach the far larger group who do not.

“What we can—and should—do changes completely depending on how we define the industry.”

If Yamanashi Meijo were merely a “sake manufacturer,” the market would seem limited. But if the business is redefined as “alcohol production,” “food manufacturing,” or even “creating joy,” the market becomes one of trillions of yen.

“With that broader perspective—and with the global market open to us—I’m convinced sake is a growth industry.”

This belief fuels collaborations that transcend categories, including a partnership with Alain Ducasse, a master chef of French cuisine, tie-ups with international hotels, and initiatives with Diners Club.

“It’s important to step into the batter’s box again and again, even if you strike out. The only way to pass on tradition is to challenge ourselves every day.”

Asked about the outlook for sake in 10 or 50 years, Kitahara answered:

“It’s incredibly bright. As Japanese cuisine spreads globally, demand for sake will grow. One day, more than half of Japan’s sake production might be exported.”

Yet he also acknowledges challenges, especially securing domestic rice amid an aging farming population. He recently founded an agricultural corporation to begin cultivating rice himself and is planning new ventures that combine sake brewing with hospitality—similar to the winery cultures of Bordeaux or Burgundy.

The future of sake will rely not only on inheritance or innovation alone, but on both working hand in hand. Listening to Kitahara—who sees sake as a growth industry and continues to embrace new challenges—we catch a glimpse of a future in which the flame of sake can burn brightly again.

Catalog

Fujiwara Techno-Art develops machinery and plants for about 27 countries around the world, and exports comprehensive technologies including design, manufacturing, installation, and follow-up services. Some of the products introduced in this article have also been exported overseas.

Contact Us

フォームが表示されるまでしばらくお待ち下さい。

恐れ入りますが、しばらくお待ちいただいてもフォームが表示されない場合は、こちらまでお問い合わせください。